In the authorised biography of Paul MacCartney, Many Years from Now, Barry Miles discusses how Paul and his brother Mike, where country boys at heart. Like thousands growing up as Liverpool expanded into overspill estates, they were raised on the borders of country and city:

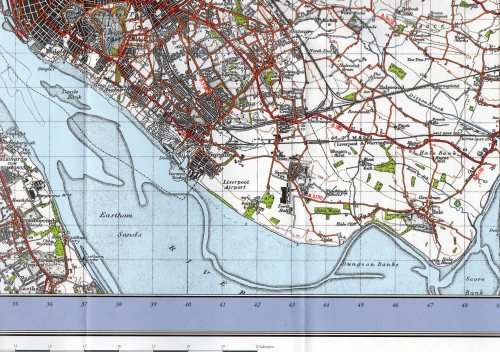

For Paul and Michael, the best thing about living in Speke was the countryside. In a couple of minutes they could be in Dungeon Lane, which led through the fields to the banks of the Mersey. The river is very wide at this point, with the lights of Ellesmere Port visible on the far side across enormous shifting banks of mud and sand pecked over by gulls. On a clear day you could see beyond the Wirral all the way to Wales. Paul would often cycle the two and a half miles along the shoreline to the lighthouse at Hale Head, where the river makes a 90-degree turn, giving a panoramic view across the mud and navigation channels to the industrial complex of Runcorn on the far side. These are lonely, cold, windy places, the distant factories and docks dwarfed by the size of the mud banks of the river itself.

In the early fifties the McCartneys moved to another new house, surrounded by a muddy building site, at 12 Ardwick Road in the expanding eastern extension of the estate. It was not without danger. Paul was mugged there once while messing about with his brother on the beach near the old lighthouse. His watch was stolen and he had to go to court because they knew the youths that did it. Paul: ‘They were a couple of hard kids who said, “Give us that watch,” and they got it. The police took them to court and I had to go and be a witness against them. Dear me, my first time in court.’

In 1953, out of the ninety children at Joseph Williams School who took the eleven-plus exam, Paul was one of four who received high enough marks to qualify for a place in the Liverpool Institute, the city’s top grammar school. The Institute was one of the best schools in the country and regularly sent more of its students to Oxford and Cambridge universities than any other British state school. It was founded in 1837 and its high academic standards made it a serious rival to Eton, Harrow and the other great public schools. In 1944 it was taken over by the state as a free grammar school but its high standards as well as many of the public-school traditions still remained.

Paul first met George Harrison when they found themselves sharing the same hour-long bus ride each day to Mount Street in the city centre, and identified each other as Institute boys by their school uniforms and caps. George was born in February 1943, which placed him in the year below Paul, but because they shared the ride together Paul put their eight-month age difference to one side and George quickly became one of his best friends. Paul soon made himself at home in the welcoming front room of George’s house at 25 Upton Green, a cul-de-sac one block away from Paul’s house on Ardwick Road.

The little village of Hale was less than two miles away, with thatched roofs, home of the giant Childe of Hale who, legend has it, was nine foot tall. Paul and Michael would stare at his grave in wonder. The worn gravestone is still there, inscribed ‘Hyre lyes ye childe of Hale’. It was a favourite destination for a family walk. On the way back Paul’s parents and the two boys would stop at a teashop called the Elizabethan Cottage for a pot of tea, Hovis toast and home-made jam. It was a pleasant, genteel interlude, a touch of quality before they walked back to their very different life among the new grey houses and hard concrete roads of the housing estate.

‘This is where my love of the country came from,’ Paul said. ‘I was always able to take my bike and in five minutes I’d be in quite deep countryside. I remember the Dam woods, which had millions of rhododendron bushes. We used to have dens in the middle of them because they get quite bare in the middle so you could squeeze in. I’ve never seen that many rhododendrons since.’ Sometimes, how-ever, rather than play with his friends, Paul preferred to be alone. He would take his Observer Book of Birds and wander down Dungeon Lane to the lighthouse on a nature ramble or climb over the fence and go walking in the fields.

PAUL: This is what I was writing about in ‘Mother Nature’s Son’, it was basically a heart-felt song about my child-of-nature leanings.

And George Harrison in The Beatles Anthology (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2000):

By this time I’d met Paul McCartney on the bus, coming back from school. In those days they hadn’t brought the buses into the housing development where I lived, so I had to get off the bus and walk for twenty minutes to get home. Paul lived close by where the buses then stopped, on Western Avenue. Just nearby was Halewood, where I used to play in the fields. There were ponds with sticklebacks in. Now there’s a sodding great Ford factory there that goes on for acres and acres.

Both George and Paul record their memories too that Speke was far from all roses.