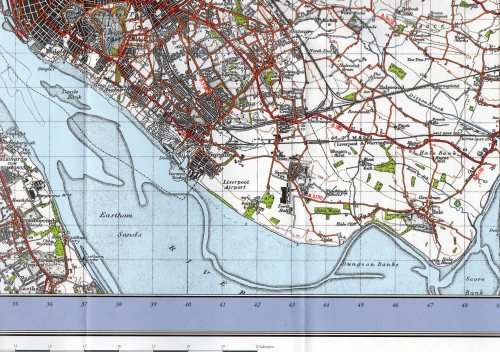

Academic and local historian with specialist interest in working class history, Eric Taplin’s Near to Revolution is a ‘must read’ for anyone interested in the 1911 strike which brought Liverpool to a standstill, and which one journalist described “as near to revolution as anything I have seen in England.”

Taplin is careful to put the events of August 1911 into a proper context, but he introduces his book by noting that,

The efforts of ordinary people to improve their standard of life and to secure greater dignity and recognition of their role in society have been evident in British history since at least the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

Writing in 1994 Taplin observes that:

Over the last fifteen years trade unions in Britain have been driven to the defensive by successive Conservative governments. Anti-union legislation has led to a loss of influence, membership and status. This is not the first time in British history that organised labour has faced severe challenges and I am hopeful that this book will be a timely reminder of the rich heritage of struggle by working people to secure protection against the excesses of ‘market forces’ through the strength and influence of the trade union movement.

The book itself is largely a well annotated collection of photographs taken during the stroke and these are preceded by an introduction which outlines the causes and the course of the strike, although Taplin points out the complexity of this and makes clear that he only offers a brief summary. He also locates the strike, which began with seafarers and spread to all other trades and jobs associated with transport, and sympathetic workers beyond transport, within the disjointed growth of unions generally, the Labour Party, sectarian divisions and the concept of a united working class. Mitigating against communalism was the prevalence of prohibition of union membership by employers, and a totally understandable individualism in the context of casual labour.

Years of festering grievances held by all sectors of the work force seemed united here though, and the sheer scale of protest and actions took employers and ‘the authorities’ by surprise. Extra police were drafted in from Leeds and Birmingham, and 2,300 army troops, these to be the forces that over-reacted on “Bloody Sunday’ causing many injuries, followed by two protestors being shot dead by the soldiers en route to Walton Jail with five prison vans. The Government sent in HMS Antrim to anchor in the Mersey.

There is a superb piece on the site of the ever-meticulous and professional historian Mike Royden, by William Jones then at Lancaster University who corresponded with Taplin as part of his research. It’s got a wealth of references. Here’s an extract which sets some of the national context for working class life in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Leo Chiozza, in his book, (Money, Riches and Poverty) published in 1905, highlighted the great disparity in the distribution of wealth amongst the people of Britain. He divided the British national product into two equal halves, one half was shared by over 39 million people, (80% of the population), whilst the remaining 5.5 million (only 12% of the population) shared the other half. Furthermore ownership of capital was distributed even more disproportionately, 120,000 people owned two thirds of the nation’s capital. Chiozza calculated that in 1905, 650,000 of the poorer sections of society left bequests totalling 30 million, whilst 260 million was left by the upper classes, 26 leaving bequests which equalled the total of the poorer sections of society.

A major concern to the government of the day, was the disproportionate distribution of wealth in the Golden Edwardian Age. Large numbers of the population lived in widespread poverty, and resulted in people suffering health problems caused by a poor diet. It was popularly believed that this had led to large numbers of men being rejected as volunteers to join the army during the Boer War because of their poor physical condition. This theory was later disproved as a myth by Michael Rosenthal in his book The Character Factory. The actual working class was divided into two main bodies, the artisans who earned a relatively decent wage and the labourers, consisting of unskilled workers, such as the dockers, porters and scavengers. Many of the unskilled workers had become members of ‘New Unions’ from the late 1880s onwards. The leaders of these new unions were often socialists who wanted to expand trade unionism on a class basis and supported the development of independent labour politics and a party to represent the working class movement.

Charles Booth (London), and Seebohm Rowntree (York), independently highlighted the state of poverty and the ill health of people in the latter part of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. Housing conditions were often appalling, people lived in extremely cramped inner city dwellings often without any form of sanitation. The greed of some landlords, who exploited people’s needs to live in the inner cities by subdividing properties and increasing rental charges, without undertaking any repairs or improvements, was common place. The cramped and unsanitary conditions people lived in were often greatly increased by tenants sub-letting rooms within their rented accommodation. Eleanor Rathbone investigated social and industrial conditions within Liverpool c1900-1910, 7 and her data highlighted the plight of the Liverpool casual labourer, and corroborated the findings of Booth and Rowntree.

In the first decade of the new century real wages fell by roughly 10%, in a situation where prices were rising while money wages tended to remain static. Food prices and the cost of living in general during this period rose steeply which, together with the fall in wages, pushed more people into poverty. Union membership increased quickly from 1,997,000 in 1906 to 3,139,000 in 1911, and the number of strikes also doubled during this period from 479 to 872, affecting three times as many workers. These strikes were led by railwaymen, miners and dockers, particularly in the heavily industrialised areas of South Wales, the North West and the North East.

Militancy increased from 1907, riots occurred in Belfast as carters, coal porters and dockers went on strike over low wages. The Scottish miners’ dispute of 1909 and the cotton, boilermakers and miners strikes of 1910 preceded further serious unrest, commencing in 1910 with the miners’ strike in Tonypandy South Wales when 12,000 miners struck for better pay and conditions against the Cambrian Coal Combine. Fifteen thousand workers went on strike over pay and conditions in the wool trade industry in Yorkshire, and further riots had occurred as a result of a strike by steel workers at Shotton on Deeside.

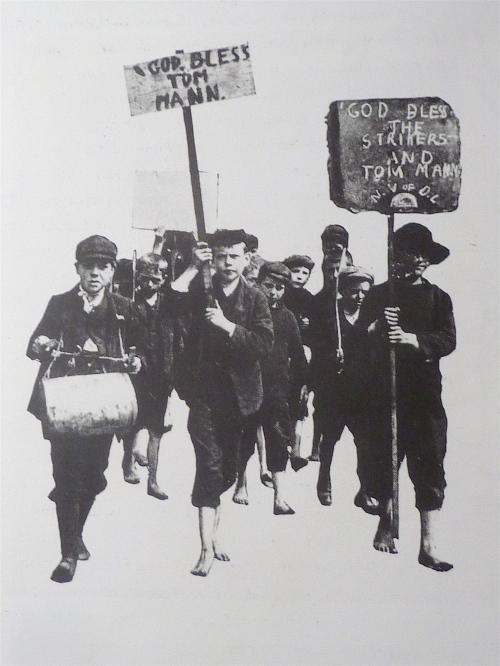

Liverpool was a hotbed of militant unionism, an example being the strike, of the ship scalers and cementers who struck on the 9 January 1911 for better pay and conditions, and were still on strike into March of 1911. Many of the new unions had been influenced by a revolutionary form of trade unionism, known as syndicalism, led by the charismatic Tom Mann and Ben Tillett. Syndicalists argued that the workers who operated the machinery possessed the real power and once the working class agreed to act together it would hold the power.

Support for Tom Mann, militant activist and socialist, and a key figire in the dispute

Call to Socialism

Read Full Post »